Adaptogenic herbs are everywhere these days, offering promises of being the ultimate cure for fatigue and the secret to boundless energy. But here’s the truth: adaptogens are one of the most misunderstood and misused herbal remedies out there these days.

When used incorrectly, they can backfire, potentially worsening fatigue instead of helping it. Many people fall into the trap of misusing these herbs, chasing quick fixes without addressing the underlying causes of their exhaustion. To truly address fatigue, you need to dig deeper to understand what’s draining you, how adaptogens work, and where they fit into your recovery plan.

In today’s blog post, you’ll learn:

- Three common causes of fatigue and how to fix them

- How Russian scientists coined the term adaptogen, and how they originally used them

- What adaptogens can—and cannot—do for your health

- The five biggest myths about adaptogens and the truths that debunk them

- The three categories of adaptogenic herbs and how to choose the one that best suits you

Table of Contents

One of the main reasons people visit the doctor these days is because of fatigue. This isn’t surprising, given how fast-paced and high-stress life has become. As herbalists, we need to develop strategies to support clients dealing with fatigue, since you will undoubtedly meet with many people where fatigue is their primary complaint.

It’s important to understand both the physiology of fatigue and the cultural factors contributing to it. Herbal medicine can play a significant role in breaking the fatigue cycle. For this, people may ask you about a class of herbs known as adaptogens.

Adaptogens are incredible plants but are probably the most misunderstood group out there. Many people aren’t clear on what adaptogens are, what they do, or, most importantly, when it’s appropriate to use them—especially when struggling with fatigue.

Often perceived as a cure-all, adaptogens are mistakenly considered a free energy source that works regardless of lifestyle or diet. However, there are many aspects of fatigue that adaptogens don’t address and, in some cases, can even worsen. So, let’s start at the beginning: why do we feel fatigue?

The Roots of Fatigue

There are different stages of fatigue. You can feel fatigued simply from staying up too late and waking up too early. This is short-term fatigue with an obvious cause and an easy remedy—a good night’s sleep.

With chronic fatigue, however, there’s constant physical and psychological exhaustion, leaving you feeling tired all the time, even when you get enough sleep each night. This isn’t the same as feeling a bit sleepy or irritable, rather it’s a deeper state of chronic fatigue that affects your work performance, family life, and both psychological and emotional health. Our cultural model and lifestyle habits don’t help this pattern either. So what can we do about it?

Let’s start by exploring the obvious causes of fatigue, the first being lack of sleep. When you’re tired, people often ask how many hours you slept. Equally important (if not more), is sleep quality since you need to reach a deep level of sleep to receive its restorative effects.

Nowadays, not only are people sleeping fewer hours, but the quality of sleep is also going down. Staring at screens until we fall asleep definitely isn’t helping, but even waking up throughout the night to urinate or eat for example, prevents you from reaching those deeper, restorative sleep stages—even if you’re technically in bed for eight hours. This is typically characterized by delta brain waves.

When someone talks to you about their fatigue, remember to ask about their sleep quality, not just the hours they slept. The best way to ask this question is, “How do you feel when you wake up? Do you feel well-rested?” If the answer is no, it’s time to investigate their sleep quality beyond counting hours.

Another reason fatigue is so prevalent is that people push themselves beyond their physiological limits until exhaustion hits. This is incredibly taxing on the neuroendocrine system, especially over prolonged periods, and is closely linked to chronic stress. Being in a constant fight, flight, or freeze mode takes a real toll on your body physiologically, not to mention psychologically and emotionally. People talk a lot about how to slow down the progression of aging but fail to address that chronic stress speeds up aging, taxes the endocrine system and affects the function of the sympatho-adrenal system, where the sympathetic nervous system and the adrenal glands work together. Prolonged stress depletes the body on many levels and is a major component of chronic fatigue, poor cognitive function, impaired digestion, and a weakened immune system.

From an astrological perspective, this ties into the influence of the planet Mars, which governs the stress response, the sympatho-adrenal system, the blood, and the immune system. When one of these areas is overworked, the others can fall into deficiency, and vice versa. As the stress response becomes more balanced, the immune system becomes more resilient and efficient. When the stress response is highly active, we also see a thwarting of the digestive fire and the blood away from the core and into the periphery. This affects our ability to digest and absorb nutrients, nourish and detoxify the liver, and balanced and even blood distribution throughout the body.

The third factor contributing to chronic fatigue may be less obvious but is critically important. When it comes to energy production, many people assume their “burned-out adrenals” are to blame. However, it’s often not your adrenals at fault. While your adrenals provide bursts of energy in response to stress by releasing adrenaline, noradrenaline, and cortisol, they’re not responsible for your constant flow state of energy. That’s the job of the mitochondria, known as the powerhouse of the cell, which produces ATP (adenosine triphosphate).

ATP is our primary source of cellular energy and is generated through a biochemical cycle called the Krebs cycle. Critical nutrients are necessary for this cycle to produce adequate ATP and sustain energy levels, including magnesium—often deficient in modern diets due to depleted soil—B vitamins, and amino acids from protein. Without enough nutrients and protein, the Krebs cycle can’t function properly, affecting mitochondrial health and overall energy. While amino acids don’t directly feed the Krebs cycle, they do break down into intermediates that ultimately feed it.

If you have a nutrient deficiency, adaptogens won’t address the root cause of your fatigue. No amount of Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera), Eleuthero (Eleutherococcus senticosus), Rhodiola (Rhodiola rosea), or Asian Ginseng (Panax ginseng) will compensate for a lack of essential nutrients that keep the Krebs cycle running smoothly. This is why it’s important to always assess someone’s diet and digestion before making herbal recommendations. Without addressing sleep and nutrition, adaptogens alone will miss the mark.

Adaptogen deficiencies don’t exist, but nutrient deficiencies do. Before giving an adaptogen to someone to relieve their fatigue, remember these three keys: quality sleep, eating a nutritious diet (or repleting nutrients with supplements if needed), and stress management techniques. Although adaptogens are not a one-stop-shop for fatigue, they have their place in managing fatigue. The important thing is to not forget about the other critical elements first.

Last but certainly not least, it’s important to mention that chronic fatigue can sometimes signal a more serious health condition, such as chronic inflammation, immunodeficiency syndrome, C. Diff., post-viral syndrome, or even cancer. Food intolerances can be an underlying culprit of fatigue too. There’s a lot of investigative work you need to do before you start suggesting adaptogens to someone. With these foundational points in mind, let’s delve into adaptogens: what they are, what they are not, their properties, and their potential benefits in addressing fatigue.

What Are Adaptogens?

The term “adaptogen” was coined by Russian scientists in the mid-20th century as they researched ways to boost productivity and performance in workers, military personnel, and athletes without resorting to amphetamines. For an herb to be classified as an adaptogen, it must meet specific criteria. Adaptogens are not catch-all herbs that “do everything” despite being described and used this way today. For example, some people call Cannabis an adaptogen, but it does not meet the foundational criteria and is therefore not an adaptogen.

There are three main qualities an herb needs to have to qualify as an adaptogen. First, it has to have a nonspecific action that enhances your body’s resilience to various stressors—environmental, physical, psychological, and emotional. Although this might sound vague, scientists historically measured this quality using tests like the swim test on mice, when they gave some mice adaptogens and others not, and compared how long each could tread water before losing strength and sinking to their sorry death.

Second, an adaptogen must be non-toxic. If an herb has a risk of toxic side effects, it’s not an adaptogen. Third, it should help the body maintain homeostasis by regulating organ function. These three traits may sound vague, but that vagueness is also a quality of adaptogens. They improve your resilience without a hyperspecific biochemical action taking place. Each adaptogenic herb is unique but completely fits each of these three requirements.

The most accepted modern theory for how adaptogens work is that they primarily influence the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the sympathoadrenal system (SAS)—note, this is not just your adrenal glands! These interconnected endocrine processes are incredibly complex, interwoven, and play a major role in managing your body’s stress response by affecting the nervous, endocrine, immune, and cardiovascular systems. Rather than targeting a single gland or organ, adaptogens support widespread physiological systems to help your body adjust to changing circumstances with greater ease.

On a biochemical level, adaptogens impact markers like catecholamines, cortisol, serotonin, nitric oxide, and various immune-related molecules (like eicosanoids and cytokines), and can also influence sex hormones in some, like testosterone and estrogen. All adaptogens impact the body thematically in this way, but no two adaptogens are the same. Each has its own unique qualities.

Some are calming, others are stimulating; some are warming, while others are cooling. Certain adaptogens affect the nervous system more, while others support cardiovascular or immune functions. Understanding these nuances is crucial for helping you select the right adaptogen for someone’s specific needs.

We don’t just give adaptogens for fatigue—we give them to someone with a broad constellation of symptoms best addressed by a specific adaptogen that matches that pattern. Adaptogenic herbs also aren’t just adaptogens—they come with other properties that differ from herb to herb. While some stimulate the nervous system, others can be calming. Dosage plays a major role too, with low doses of some herbs being relaxant and larger ones stimulating.

Some adaptogens have nootropic properties that support cognitive health, aiding focus, concentration, and memory. Others modulate inflammation and profoundly impact the immune system through immune-amphoteric or immunoregulating qualities. This means they fine-tune immune function by balancing deficiencies and excesses—especially relevant for autoimmune conditions, which often feature a complex blend of immune overactivity and deficiency. Such immune dysregulation creates chronic inflammation, which imposes ongoing physiological stress on the body, significantly affecting the HPA axis and the sympathoadrenal system. People often think stress is psychological or emotional, but your body can also be stressed from a long run or chronic inflammation. Adaptogens work on all of these aspects of stress.

Many adaptogens contain high amounts of antioxidants, though not all antioxidants are adaptogens. Research has shown that adaptogens may even protect mitochondria through mechanisms involving heat shock proteins. We’re still in the early stages of fully understanding the biochemical pathways adaptogens influence so this is all conjecture, but it’s still interesting to know.

There’s some overlap between adaptogens and traditional herbal classifications in Eastern systems of herbal medicine. In Ayurveda, the term rasayana describes rejuvenating herbs that strengthen and build the body or organ systems. In Traditional Chinese Medicine, tonics such as qi tonics or Kidney yin and yang tonics tend to have similar effects as adaptogens. But, while there is overlap between these tonic and rasayana herbs and adaptogens, not all rasayanas or tonic herbs are necessarily adaptogenic, so it’s important to not just lump these categories together as there are distinctions.

Adaptogen Myths and Misconceptions

There’s a lot of information out there about adaptogens, but a lot of it comes from marketing campaigns, not science nor tradition. So before we dive into talking about specific adaptogenic herbs, let’s do some myth-busting.

Myth #1: Adaptogens benefit everyone.

When someone says this to you, that’s your signal to run in the opposite direction. The adaptogenic marketplace is massive nowadays, and profit is often prioritized over integrity, knowledge, or understanding. Someone who tells you this may not have bad intentions, but they aren’t qualified to advise you on how to use them safely.

Myth #2: You can use all adaptogenic herbs interchangeably

The idea that all adaptogens are interchangeable is oversimplified since each adaptogen has unique characteristics that fit different constitutions and clinical patterns. As in all situations of applying herbal medicine, specificity is truly the key to success and not all herbs in this category are the same.

Myth #3 Adaptogens are a free source of energy

Adaptogens are not panaceas and will not heal you of everything, give you unlimited free energy, or fix bad lifestyle habits. They can’t replace a healthy lifestyle, good sleep, and proper nutrition. In other words, they won’t work if you don’t do your part.

Myth #4 Any herb can be an adaptogen

There’s a trend of classifying popular herbs as adaptogens when they don’t actually meet the technical criteria. For example, herbs like Turmeric (Curcuma longa), Cannabis (Cannabis sativa), and Gotu Kola (Centella asiatica) are sometimes labeled as adaptogens, even though they don’t have the properties required to define them as such. Another common misunderstanding is confusing adaptogens with the term amphoteric, which are herbs that modulate different bodily functions but are not necessarily adaptogenic.

Myth #5 There is zero harm associated with taking adaptogens

Adaptogens are great herbs, but they still have dangers associated with them if misused. A common mistake I see people making is taking them in great excess, whether in terms of dosage, frequency, or highly concentrated extracts. This can push people beyond their natural limits, leading to long-term burnout. For example, athletes using adaptogens like Cordyceps may see short-term gains but suffer from deeper fatigue if they keep pushing against their physiological limits. We can think of this as an enabling effect which can actually lead to further athletic burnout.

When overused, adaptogens can suppress your symptoms of exhaustion. While this may sound like a good thing superficially, it only means that you won’t be able to address the root cause and can worsen your fatigue even more over time. This can be dangerous if your fatigue is a sign of something much more serious that needs medical attention.

Lastly, taking high doses of adaptogens can be overstimulating and cause anxiety, jitteriness, or insomnia—similar to the effects of caffeine. With so many highly concentrated extracts on the market, it’s easier than ever to overdose with them.

David Winston, a renowned herbalist and personal teacher, wrote a book about adaptogens. There, he categorizes adaptogens into three levels based on available research:

- True Adaptogens: The best-studied and confirmed adaptogens.

- Probable Adaptogens: Herbs that likely meet the adaptogenic criteria but lack sufficient scientific confirmation.

- Possible Adaptogens: Herbs traditionally used in ways that suggest adaptogenic qualities, though they lack scientific validation to back it up.

Instead of giving someone a handful of random adaptogens, you will see more success with a targeted approach. Less is more, and you can see better results with a single well chosen adaptogen and a holistic plan rather than throwing every adaptogen in a bottle. Moreover, you can enhance the effects of a single adaptogen by pairing it with other herbs. For example, with nervines that relax and calm or nootropics that improve focus and concentration.

I also consider affinity-based trophorestoratives. For example, if a client has both fatigue and an underlying heart condition, use heart-supportive herbs like Hawthorn (Crataegus monogyna) or Night Blooming Cereus (Selenicereus grandiflorus). For cases where nervous system burnout precedes endocrine depletion (which is often the case), consider Milky Oat seed (Avena sativa). If the immune system is depleted, look into Astragulus (Astragalus membranaceous), which is an immune trophorestorative. Lastly, if the liver needs support, Milk Thistle (Silybum marianum) is helpful as a liver trophorestorative.

Because fatigue is often the result of physically, emotionally, and psychologically overextending yourself, I recommend using indicated nervine relaxants, sedatives, and trophorestoratives first to support deep and restful sleep, and improving diet to correct deficiencies before jumping to adaptogens.

Finding the Right Dosage with Adaptogens

When it comes to adaptogens, dosage is key. You want enough to feel a subtle, balanced effect—not too much that you feel overstimulated or too little that you feel nothing at all. To make matters even more complicated, each adaptogen has a unique dosage range.

For example, Asian Ginseng is a stronger adaptogen. In tincture form, taking a standard 1:5 strength ratio dosed at around 1-2 milliliters, three times a day provides potent yet balanced effects. Eleuthero, on the other hand, is much gentler and can be used at a higher concentrations and dosages. Eleuthero tinctures, often prepared at a 1:4 strength, can be dosed at 5 milliliters, four times a day—much higher than Asian Ginseng.

Eleuthero is interesting because it was the original herb studied by Russian scientists for its adaptogenic qualities. The original Eleuthero formulations were incredibly strong at 1:1. This highly concentrated form is much stronger than the common 1:4 or 1:5 tinctures you can make at home. The reason why some people take Eleuthero but don’t feel any effects is because they’re taking too low of a dose. 30 drops of a 1:5 tincture simply isn’t enough. But if you try one of those concentrated fluid extracts, you’ll undoubtedly feel the difference. Your dosage can make the difference between not feeling an adaptogen at all, feeling overstimulated from it, or feeling its effects just right.

A good rule of thumb is that if you feel jittery or overstimulated after taking an adaptogen, it means your dose was likely too high. Adaptogens should bring you a sense of stable energy, as if you have nourished your vitality—feeling awake and balanced, not wired or exhausted. Remember, adaptogens don’t “give” you energy—they work with your body’s vital force by making it more replete. If you use adaptogens to give you energy and you use that energy to push yourself beyond your physiological limits, you will only drive yourself into deeper exhaustion.

Finally, remember that adaptogens are most effective when combined with a healthy lifestyle and dietary practices. Without a foundation of good nutrition, rest, and stress management, adaptogens can only go so far. If used strategically in part of a larger plan, they can help support your body’s natural balance and enhance vitality.

A Guide to Adaptogens: Choosing and Using the Right Herbs

When it comes to adaptogens, not all are created equal. Some are classified as true adaptogens, while others are considered probable or possible adaptogens based on their strength and specific effects. Here’s a breakdown of the categories and some details that tell you more about what makes each adaptogen unique. This categorization is based on the work of David Winston (RH).

True Adaptogens

True adaptogens are the most widely recognized for their ability to support resilience and balance in the body. These include:

- American Ginseng (Panax quinquefolius): Moistening, mild, and suitable for people with a dry constitution.

- Asian Ginseng (Panax ginseng): Typically warming and drying; the red form is particularly strong and stimulating, while the white Ginseng is a bit gentler and more moistening. Classically this plant was reserved for people over the age of 60-65.

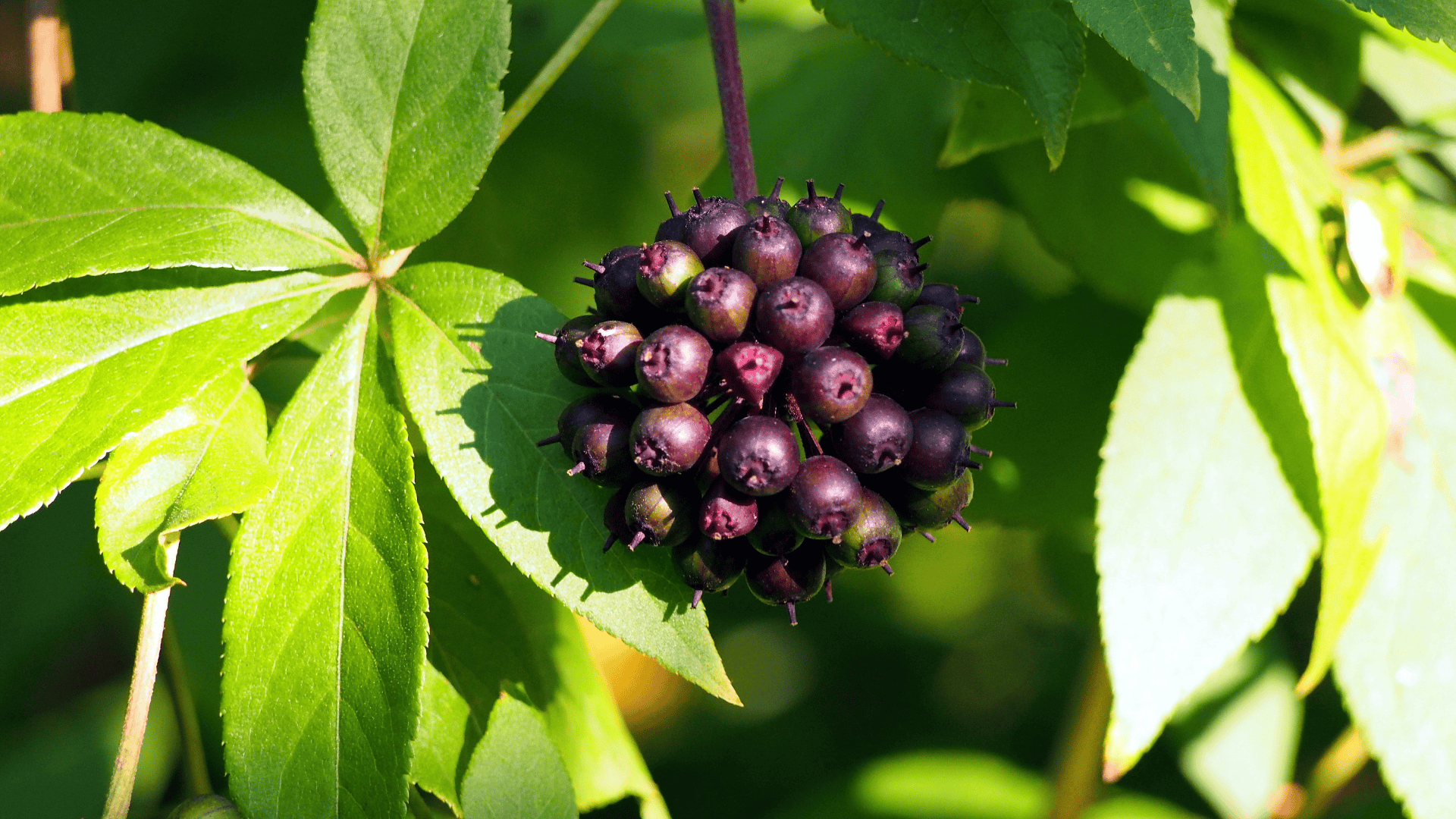

- Eleuthero (Eleutherococcus senticosus): Also known as Siberian Ginseng, this is generally milder and adaptable for a wider range of people, especially those of a younger age.

- Rhodiola (Rhodiola rosea): This herb is very drying and astringent, and can be overstimulating for many. I consider it the most stimulating adaptogen.

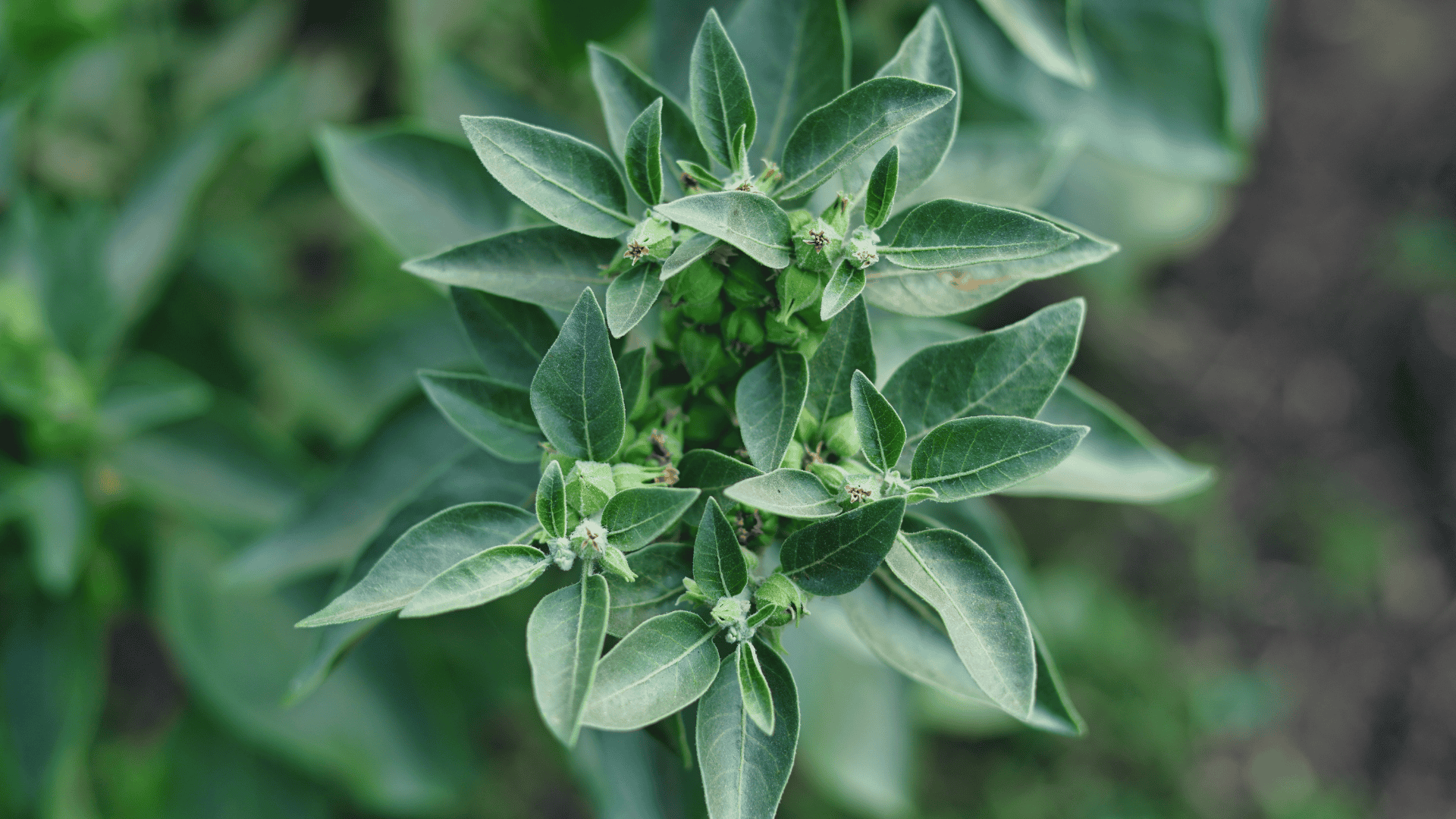

- Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera): Strong yet gentle, supports the nervous system, and supports muscle and muscle-related autoimmune conditions, like myalgias. It is considered calming but can stimulate in higher doses.

- Schisandra (Schisandra chinensis): Antioxidant, astringent, and drying, a liver tonic, lung trophorestorative, and excellent for cognitive function.

- Cordyceps (Cordyceps sinensis): Known for respiratory support and energy without overstimulation at moderate doses, excellent immune support.

- Shilajit: Not an herb but a mineral-rich pitch traditionally sourced from the Himalayas, known for its revitalizing properties

Probable Adaptogens

Some herbs are not fully classified as adaptogens but show promising adaptogenic qualities. For example:

- Holy Basil (Ocimum sanctum): A versatile nootropic herb with immune, digestive, and nervous system benefits, along with notable blood sugar regulating properties.

- Shatavari (Asparagus racemosus): Moistening, nourishing, and strengthening, especially helpful for female reproductive health. This is a classic female rasayana in Ayurvedic medicine.

- Codonopsis (Codonopsis pilosula): Known as “poor man’s Ginseng,” it is a gentler, more affordable alternative to Ginseng.

- Reishi (Ganoderma lucidum): A powerful immune modulator, less direct on energy but highly beneficial for respiratory and liver health.

There are lots of other herbs in the Traditional Chinese Medicine Materia Medica that are generally considered probable adaptogens, such as Tienchi Ginseng, Cynomorium (Suo Yang), Cistanche (Rou Cong Rong), and Morinda (Ba Ji Tian).

Possible Adaptogens

- Maca (Lepidium meyenii): I tend to consider this more of a food than an herb. It should thus be taken in higher doses.

- Licorice root (Glycyrrhiza glabra): Very moistening, respiratory affinity, cortisol sparing to prolong its effects

- Jiaogulan (Gynostemma pentaphyllum)

- Guduchi (Tinospora cordifolia)

Not all adaptogens are created equal, and it’s important to understand their differences. Some are calming, like Ashwagandha, Schizandra (in low to moderate doses), Jiaogulan, and Cordyceps—though, in high doses, both Schizandra and Cordyceps can become stimulating. Other adaptogens, like Rhodiola, red Asian Ginseng, and American Ginseng, are naturally more stimulating, especially at higher doses. Eleuthero is another example, often milder but capable of a stronger effect at elevated doses. Rhodiola is the most stimulating, with red Asian Ginseng and American Ginseng following.

Some adaptogens are moistening, like American Ginseng, white Asian Ginseng, Shatavari, and Cordyceps, whereas others, like Rhodiola and Schizandra, are very drying and astringent—qualities often overlooked. This is why it’s important not to give Rhodiola to someone already dry, as it will only exacerbate their dryness further.

From an energetic perspective, most adaptogens are warm to hot in nature, with a few being cooling. Rhodiola, for example, tends toward cooling, while Eleuthero and Jiaogulan are more neutral.

Another way to determine which adaptogen is right for someone is based on age. Traditionally, the stronger adaptogens, like Asian Ginseng, were reserved for the elderly with signs of depletion, weakness, or coldness. It’s not an herb we’d give a vibrant 20-year-old. However, if someone younger has premature signs of aging due to stress, they might benefit from these herbs. Generally speaking, milder adaptogens like Eleuthero and Ashwagandha are more suitable for younger to middle-aged people.

With all this said, it’s important to recognize that giving adaptogens isn’t enough to address fatigue. I limit my usage of adaptogens when helping people to usually one, with a maximum of three, and they each need to fit the person’s needs and constitution. Adaptogens pair well with lifestyle changes, dietary adjustments, and identifying the root causes of fatigue. Often, I start with assessing food intolerances, sleep quality, nutrient levels, and chronic stressors. Supporting stress management is key, as is addressing gut health, given its close link to brain health.

Using adaptogens holistically means targeting and remedying the underlying sources of fatigue first, using replenishing herbs that help the body recover second, and using adaptogens third (and only) if the adaptogen aligns with the constitution and constellation of symptoms someone has.

When using adaptogens, selecting the specific one(s) that match the patient is key, dosage is critical, and they are always more effective when combined with other herbs in a larger protocol. By taking this careful and nuanced approach, you honor the whole person, not just treat the symptoms, and this is how you use adaptogens holistically, safely, and effectively.

For deeper studies of adaptogens, I recommend picking up a copy of David Winston’s Adaptogens book, along with Donnie Yance’s Adaptogens in Medical Herbalism. Paul Bergner also has a great audio course I highly recommend called Fatigue: Pathophysiology, Natural Therapeutics and Adaptogens.